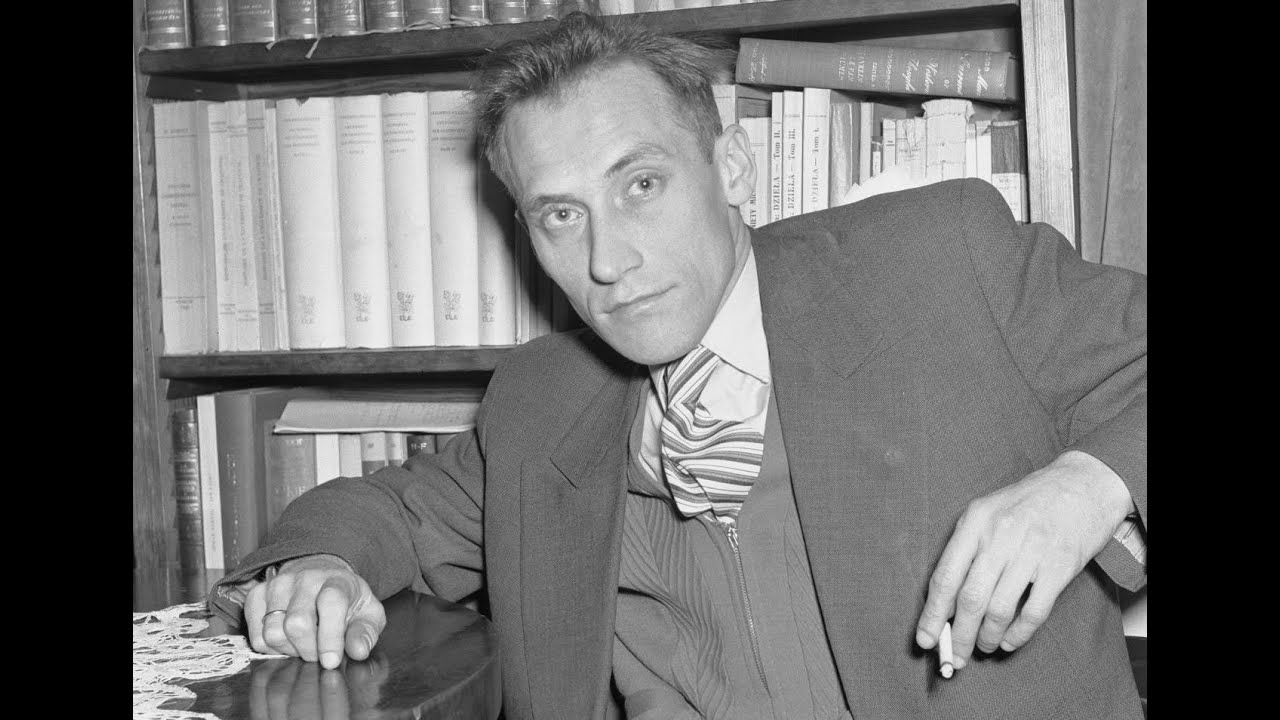

Tony Judt refers to this author, Leszek Kołakowski, as “the last illustrious citizen of the Twentieth-Century Republic of Letters.” That is an apt slogan. The depth of his knowledge and the force of his arguments are astonishing.

Volume 1 (The Founders) analyzes and penetrates all the main Marxian principles, picks them apart so we can see their component parts and what makes them tick. This is not an easy book. It is dense, very dense, but immeasurably rewarding if one wishes to understand the philosophical underpinnings of Marxist thought, the ways in which Marxism was and is innovative and useful, and where Marxist theories fall short (sometimes disastrously short). Among other things, this book contains the most elegant dismantling of Marx’s theory of historical materialism that I have ever read.1 I feel as if I am looking upon the very pinnacle – the mountaintop – of scholarship and erudition. All I can do it bow my head and acknowledge the greatness of it. I am like an amateur composer listening to a Beethoven concerto. Crucially, Kołakowski does not set out to embarrass Marx, but instead respects him for the pioneer that he was, for his far-seeing vision and dazzling analytical prowess. But Kołakowski does subject Marx’s ideas to a forensic analysis that lays bare all the gaps and missteps, and opens up many questions with which Marxists must wrestle: Does Marxist analysis have any scientific value? Do Marx’s ideas on value and history have anything useful to tell us about the real world? Does Marxism invariably slip into totalitarianism, regardless of the best intentions of its adherents? These are questions Marxists have been exploring for a century, and I intend to do the same.

In Volume 2 (The Golden Age), Kołakowski’s aims his all-seeing eye at Leninism, a philosophical tradition absolutely bursting with contradiction and double-talk. Kołakowski’s scientific approach to philosophy somehow juxtaposes just fine with his sharpened polemical abilities. It’s as if the scientific inquiry delivers the verdict that Leninism is an unrealistic, violent, contradictory, and exploitative ideology; for Kołakowski, there is no shame in confidently sharing the results of a scientific inquiry. His withering indictment of Lenin’s method, his philosophical rigor, his honesty, his prophesies, and his misguided actions once in power lay bare the moral and intellectual bankruptcy of Leninism as a system of thought. Lenin the man is revealed to be a boor, a liar, a tyrant, a power-hungry despot, and a poor philosopher. Kołakowski does not draw these conclusions explicitly, but instead allows the reader to do so.

Perhaps Kołakowski is a masterful propagandist who possesses the ability to incept these opinions into the reader’s brain, but I don’t really believe that. Instead he just exposes various thinkers’ theories to the light, that’s all. This doesn’t mean Kołakowski is a constant critic; his analysis is so much more subtle and productive than that. If a theory has enough qualities to withstand the author’s scrutiny, it comes out stronger for it in the end. Kołakowski analyzes many Marxist ideas and traditions throughout the book, and a good portion of them – those based on sound reasoning, honest argumentation, and deep philosophical reflection – show their quality under Kołakowski’s scrutiny. It just turns out that when we shine this same light on Lenin’s theories, they wither, crack, and fall apart. They are revealed to be hollow and decrepit.

Kołakowski’s main argument, if one must be identified, is that Bolshevism did not deteriorate into totalitarianism because of Stalin (as is often argued, especially by Lenin sympathizers), but instead because totalitarianism was baked into Lenin’s philosophy from the start, despite all the noises he made about wanting to create a better democracy. Before he was even in power, Lenin fantasized about liquidating all his political opponents, using violent coercion to keep all dissenters in line, and dictating to the masses what was and was not in their best interest. He desired to create a new permanent elite (the communist party officials), but dressed it up as if he was actually abolishing all elites forever. Lenin described in giddy detail his dream of conducting mass confiscations of all private land and surplus (see Lenin’s State and Revolution), and imagined that the bulk of the people would not only celebrate these actions but assist in the mass thievery. In reality, Lenin’s first economic policy of requisitioning “surplus” grain from peasants (or what the requisitioners considered to be surplus) led to widespread mistrust of Lenin’s new state, as well as bribery and coercion. The people did not want to give up their product to the state, and the officials in charge of snatching the goods were highly susceptible to bribes. Their only carrot for making the people obey was threat of force, and use of Lenin’s massive police state infrastructure. Meanwhile all political activity that did not further the socialist revolution was anathematized.

This was not Stalinism, but Lenin’s original ideas and policies, the tactics that he used when he (Lenin) was in charge. Modern Leninists often argue that he truly fought for the good of the people, and that after his death it was Stalin who corrupted his ideas and policies, warping them into a totalitarian, violently repressive, hyper-bureaucratic police state. But Lenin was the true founder of Soviet totalitarianism. Kołakowski lays this bare without becoming overly angry in the process (something I would struggle with). Overall his critique on Lenin is devastating, yet really he lets most of Lenin’s ill-conceived ideas and shameful policies speak for themselves.

Notes:

- See: Leszek Kołakowski, Main Currents of Marxism: The Founders, The Golden Age, The Breakdown, 2nd ed., trans. P. S. Falla (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2005), 298-307. On those pages you’ll find Kołakowski’s most concentrated critique of historical materialism. Here are some of the main elements:

a) Marx’s system of historical materialism either requires we accept full economic determinism (AKA vulgar materialism) which tells us that economic forces are the ultimate cause of every aspect of society (including, for example, when a mother loves her newborn baby, and in which stanza a poet inserts a comma); or conversely historical materialism must acknowledge that economic forces are not the ultimate causes of human history, but just one of many forces which always act upon mankind. In other words, one option is so dogmatic that it defies common sense, while the other waters down the theory to such an extent that it loses its ability to prognosticate, and becomes functionally meaningless.

b) Human history is a one-off, unrepeatable phenomenon. Therefore we cannot scientifically establish timeless rules that one economic system (capitalism) must always be superseded by another (communism). This is untestable, no more than a guess. Nor can we claim that it is a proven fact that feudalism must always give way to capitalism. Though that did in fact happen at certain points in human history, there is no way to prove that it must always be this way.

c) The theory is vague. If another factor besides economics clearly exerts force on a given society, a materialist might waive it away and call it an accidental interference. This is because to acknowledge that a multiplicity of factors influence mankind is to admit that materialism does not tell the full story. But to waive away counterexamples in such a way is a cop-out, a handy way to ignore inconvenient facts. The only way to get away with it is to claim that any non-economic force which influences mankind is either an accident of history, or somehow (at its core) an outcrop of an economic force. But this makes the theory so vague that it loses its meaning.

d) Even if the theory of economic determinism is accurate, this does not automatically lead to the conclusion that capitalism must fall and be replaced by communism, or that the proletariat will inevitably attain class consciousness and develop a revolutionary outlook. Though Marxism did have a powerful influence on the workers movement (and increased class consciousness), this does not prove these prophesies true. Capitalism may in fact be with us forever. Any materialist who believes it has been scientifically proven that capitalism must fall is a believer not in science, but in prophesy.

e) The prophesies of historical materialism are based on a very hopeful and optimistic outlook about mankind and human history. They believe that someday human history will culminate in a “happy ending”. This fantastical vision is dressed up as a scientific theory, but it is more of a religious vision. If the study of human history reveals anything, it is that nothing is permanent, change is constant. To believe that communism, once established, will end the cycles of competition, innovation, change, and destruction that have accompanied mankind since the beginning of recorded history, is to believe in a feel-good myth, not so different than the belief that one day the deity will return to earth and forever end mankind’s suffering. ↩︎